How Does the Heart Work? Review Heart Structure and Function

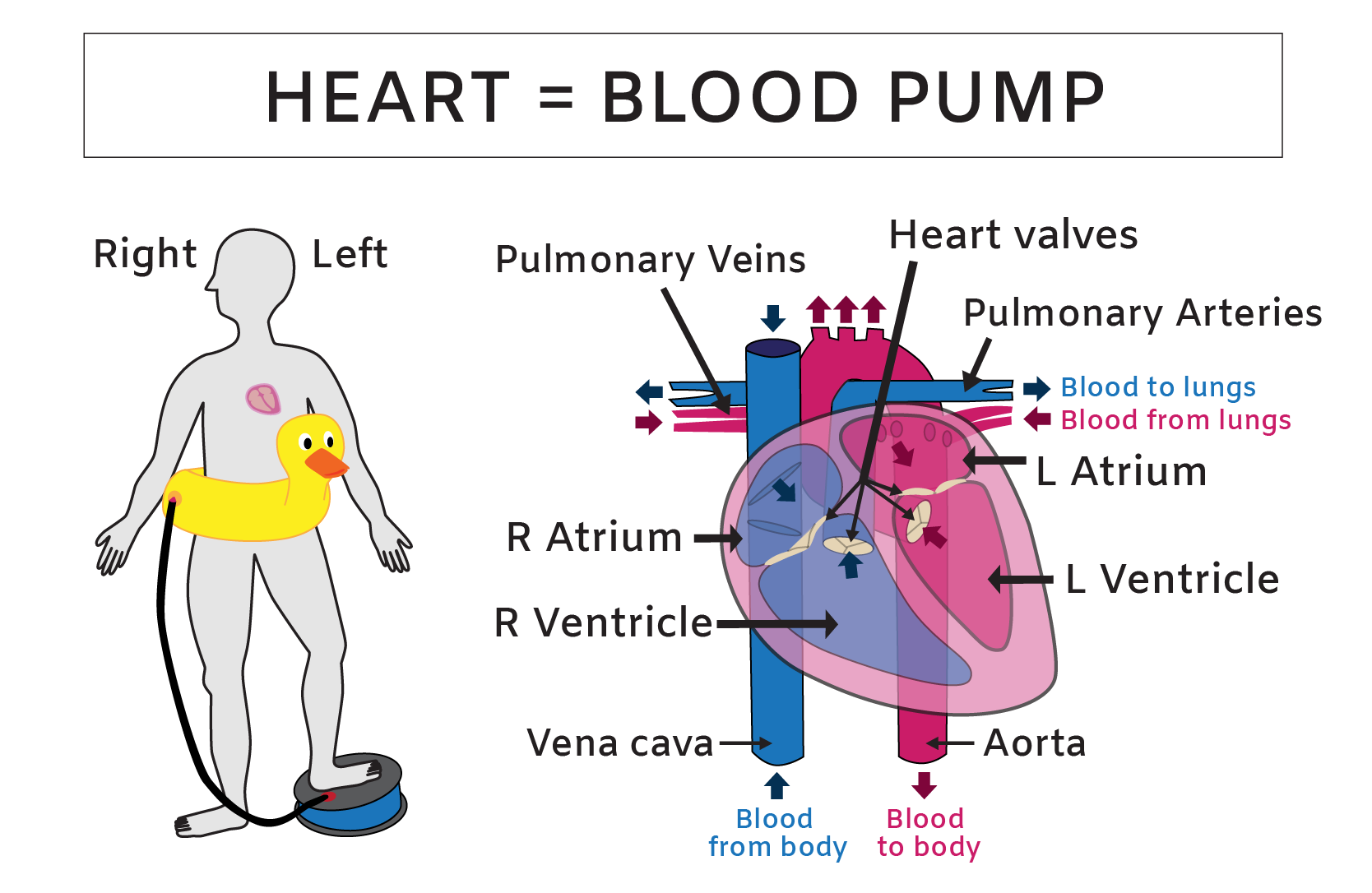

Learn More About Simplified Science PublishingThe human heart is a muscular organ that squeezes and relaxes to pump blood through its four chambers, four valves, and blood vessel tubes.

What does the heart do for your body?

The heart is your body's blood pump. It is a muscular organ that is roughly the size of your fist and it is easy to locate thanks to its constant thumping inside your chest. Take a moment to place your hand over your heart. As you feel it pulse against your palm, your heart is pumping 5-6 liters of blood through all of your internal tissues. It is remarkable that this small muscle provides the force that is necessary to bring nutrients and remove waste for nearly every cell in your body. Read on to learn more about human heart anatomy and how it supports your life.

How does the heart work?

The heart is made of specialized cardiac muscle tissue that surrounds four chambers. Essentially, the heart is a muscle with four holes in the middle and these chamber holes are attached to blood vessel tubes that allow for blood entry and exit. There are also four valves that separate the heart’s chambers and tubes and these valves ensure that blood only flows in one direction. The heart's basic function is to use these four muscular chambers to pump blood throughout all of your body.

Each heartbeat is created by muscle contractions that squeeze the chamber walls in a precise pattern. These muscle contractions provide the force that pumps blood throughout your body, similar to a foot pump that forces air into your favorite floating device. But instead of pumping air into toys for a pool party, your heart functions as a dual blood pump to support your life party. The “dual” part of the blood pump arises because the right and left sides of your heart function as separate pumps that send blood to two different destinations: the lungs and the body. The right chambers of your heart receive deoxygenated blood from your body’s veins and pump it into your lungs and the left chambers of your heart pump the recently oxygenated blood into the rest of your body.

Heart blood flow order

One way to understand the heart’s blood flow pattern is from the point of view of a red blood cell flowing through the tubes, valves, and chambers. Imagine that you’ve shrunk down to and hopped onto a red blood cell to take a tour of the heart.

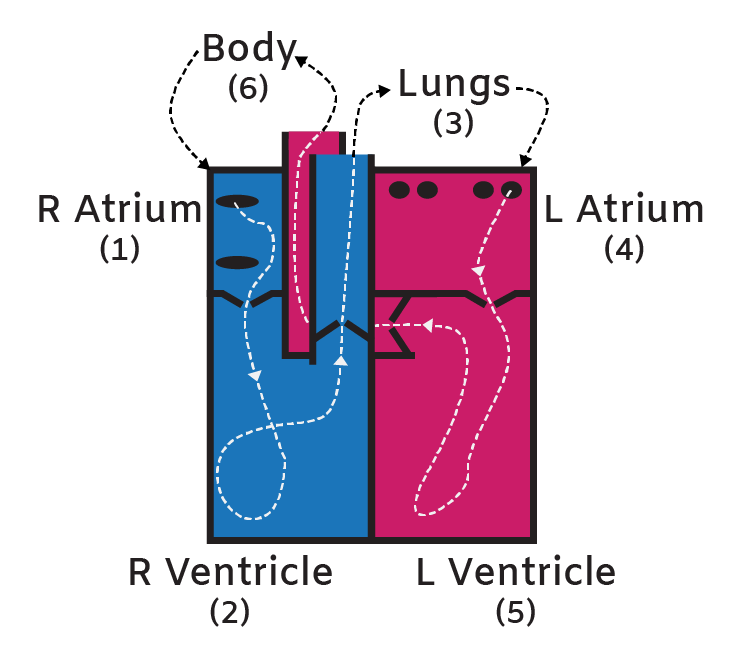

The heart blood flow journey begins in the heart’s upper-right chamber, called the right atrium (1) - See Heart Blood Flow Diagram illustration. You and your blood raft flow into the right atrium from either the superior or inferior vena cava, which are the largest veins in your body.

After reaching the right atrium, you have less than half a second before the change in pressure via the atrium contraction sends you down into the large lower-right heart chamber, called the right ventricle (2). To get from the right atrium to the right ventricle, you will have slipped through your first heart valve. Heart valves are flexible cartilage flaps that function as a perfectly timed doors and they only allow blood to move in one direction through the heart’s chambers and tubes.

After you slide through the first set of valve flaps, they slam shut behind you to prevent blood from flowing back into the atrium and the muscular ventricle walls contract. This contraction increases pressure in the right ventricle chamber and sends you shooting upward through another set of valve doors in a tube called the pulmonary artery (3).

The pulmonary artery sends you gushing toward the lungs, where it splits into many smaller tubes. You are eventually squeezed through the tiniest tubes in the lung’s alveoli one RBC at a time. Within these narrow tubes in the lungs, the RBC rafts load up with oxygen, carbon dioxide leaves the blood vessels and then you and your oxygenated buddies flow back to the heart via the pulmonary veins. One of the pulmonary vein dumps into the upper left chamber of the heart, called the left atrium (4).

Soon after you reach the left atrium, a familiar process begins again as a change in pressure or an atrium contraction sends you down through another valve and into the final chamber, the left ventricle (5). From here, you will embark on an adventure through the body because the next ventricular contraction will send you bursting upward through the final valve in the aorta (6).

The aorta is a large tube that branches into many other smaller tubes to distribute you, (and the newly oxygenated blood), throughout the body. If you decide to continue with the tour, you and your iron raft may flow down to a toe before circling your way back to the heart’s right atrium in roughly 30 seconds.

Heart contraction cycle

Cardiac cycle events are segmented into two main parts of the heartbeat: diastole (refill) and systole (pump). The diastole happens when the top chambers called atria contract together to help refill the ventricles and the systole happens with the large lower chambers called ventricles contract together to pump blood into the lungs or body. Every heartbeat that you feel is due to the repeated cycle of this refill and pump.

This repeated contraction pattern also produces two sounds that are called “lup-dub”. The “lup” sound is generated by the closing of the two valves that are between the atria and the ventricles, (which signals the end of the heart’s refill) and the “dub” is the sound made by the closing of the two valves within the pulmonary artery and the aorta, (which signals the end of the heart’s pump). These two sounds have been used extensively throughout medical history to determine whether a patient’s heart is working properly and a well-trained doctor can distinguish subtle differences in the sounds to diagnose problems such as heart murmurs and valve defects.

Human heart anatomy study guide

Heart: The heart is made of specialized cardiac muscle tissue that surrounds four chambers and pumps blood into your lungs and body.

Blood Flow: Blood low in oxygen moves from the body into the right atrium, to the right ventricle and then pumped into the lungs. Blood high in oxygen moves from the lungs into the left atrium, to the left ventricle and is then pumped out into the body.

- Reaches = Right atrium

- Leaves = Left atrium

There are two main parts of a heartbeat:

- Refill (diastole) - Blood flows from the atria to the ventricles.

- Pump (systole) - Blood is pumped from the ventricles into the lungs and the body.

Learn more about heart anatomy by reading this heart electrical system and ECGs article.

Related Content:

- Heart Electrical System: ECG and Sequence of Electrical Conduction

- What is a Heart Attack? Heart Attack Causes and Prevention Tips

- What is Blood Made Of? Review Blood Components and Functions

- How Do Arteries and Veins Work? Blood Vessel Structure and Function

- What is Aerobic Respiration and Why is it Important?

- How Does the Diaphragm Work? Diaphragm Structure and Function

References:

- Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 18th Edition. Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Jameson J, Loscalzo J. eds.

- Anatomy, Physiology, and Disease: An Interactive Journey for Health Professions , 2nd Edition. Bruce J. Colbert, University of Pittsburgh, Johnstown.

- https://www.thehealthy.com/bodies/human-body-every-minute/

Create professional science figures with illustration services or use the online courses and templates to quickly learn how to make your own designs.

Interested in free design templates and training?

Explore scientific illustration templates and courses by creating a Simplified Science Publishing Log In. Whether you are new to data visualization design or have some experience, these resources will improve your ability to use both basic and advanced design tools.

Interested in reading more articles on scientific design? Learn more below:

Content is protected by Copyright license. Website visitors are welcome to share images and articles, however they must include the Simplified Science Publishing URL source link when shared. Thank you!